1 Purpose of this architecture document¶

We first launched the project called now called nublado in 2017, as part of an investigation into whether JupyterLab would form an appropriate basis with which to create the Notebook Aspect of the Science Platform. The service rapidly became very popular among project staff some of whom quickly became reliant on it for their daily work. We thus found ourself in production with a prototype based in turn on a rapidly evolving open-source codebase, and needing to prioritise user demands and service availability. Additionally the service got adopted by critical path teams engaged in commissioning activities which resulted in a number of high availability deployments at the summit and laboratory sites.

In light of our experience, we want to undertake significant refactoring of the codebase for the following reasons:

Our upstream dependencies, particularly JupyterHub and JupyterLab have significantly evolved since the initial architecture, which means we both have unecessary code and have difficulty making upstream contributions and staying current with upstream

Following multiple deployments, we understand better the axes of configuration and have concluded that the current organisation of the codebase would make it hard for contributors outside the project to modify it for their own use.

As a prototype, the current codebase lacks necessary developer practices such as unit tests, automated build-test and instrumentation

Addressing these problems requires significant refactoring. Given the relatively small size of the codebase and the significant architectural changes, we are undertaking a blank slate rewrite in order to avoid impacting the robustness and support level of the current production deployments.

2 Major features that we need, but aren’t in upstream Jupyter¶

Here is a general list of the things that Nublado does that normal JupyterHub and JupyterLab don’t do (at least out of the box):

Gafaelfawr auth support - this is our internal auth proxy that handles login and authentication, and returns headers that contain the userid, email, and other important information.

Interactive Options Form - JupyterHub is normally configured to only load one image as a lab. In Nublado there’s an interactive options form that allows the end user to select from a list of images, and handle other configuration options at startup.

Individual namespaces - JupyterHub normally creates all labs in the same namespace in which it is running. By creating a namespace per user, we can further isolate and control the environment at the kubernetes layer.

Creating additional Kubernetes resources - JupyterHub will only start a lab pod, but we could also allow for more and different kubernetes resources to be ensured at lab creation time.

Lab Configuration - Nublado injects a lot of environment variables to configure the lab to point to other parts of the environment, such as TAP and Firefly. Some of these configuration options are needed to configure extensions and plugins. Some of these configuration options are tailored based on user information, or input from the interactive spawner.

Lab Pod Volumes - Nublado configures the pod to mount certain NFS paths so that the Lab can interact with the datasets and home directories.

Prepuller - Our images are pretty big, so this can cause issues when needing to spawn labs. It’s best if images are already downloaded and extracted on the kubernetes nodes to reduce spawning times.

Many of these could be useful to other people and depending on the feature, could be either pushed to upstream Jupyter or put into extensions for the Hub and the Lab.

3 Improved Developer Process¶

Because we have a working Nublado right now, we have given ourselves the time to work on a rewrite. But this also means that we won’t have users testing Nublado daily, and we will have to test things ourselves.

Some of the process will be style checking by tools such as black. This will enable a consistent code style across multiple developers so that the code has a uniform feel.

We will immediately implement as the first step an automated build on GitHub, to build and test changes. When new containers are built, we should push them to a Google environment for immediate testing. Since Mobu only relies on stock Jupyter features, we can immediately start to run Mobu against stock Jupyter and find bugs, leaks, and issues as close to when they were introduced as possible.

With multiple developers, having a source of truth for the builds is essential, as it doesn’t allow for forgotten files or special environments for handling builds.

These improved developer processes will not only make it easier for us to ensure our code is of good quality, but help others contribute as well. Having a way to make a change, build it, test it, and deploy it will enable people to feel safe making changes without regressions.

Another thing to mention is metrics. Both JupyterHub and JupyterLab have built in prometheus monitoring of a set of metrics on an HTTP endpoint. These metrics can be gathered by a telegraf instance from InfluxDB to store these metrics in a graphable way. Since this is a pull rather than a push, anyone can retrieve these metrics for tests or other purposes.

As we add components we should think about adding metrics about what choices were made, time spent, or errors encountered as applicable. It looks like new metrics can be added, although there might not be a way to add a metric outside of a PR (see https://github.com/jupyterhub/jupyterhub/blob/master/jupyterhub/metrics.py).

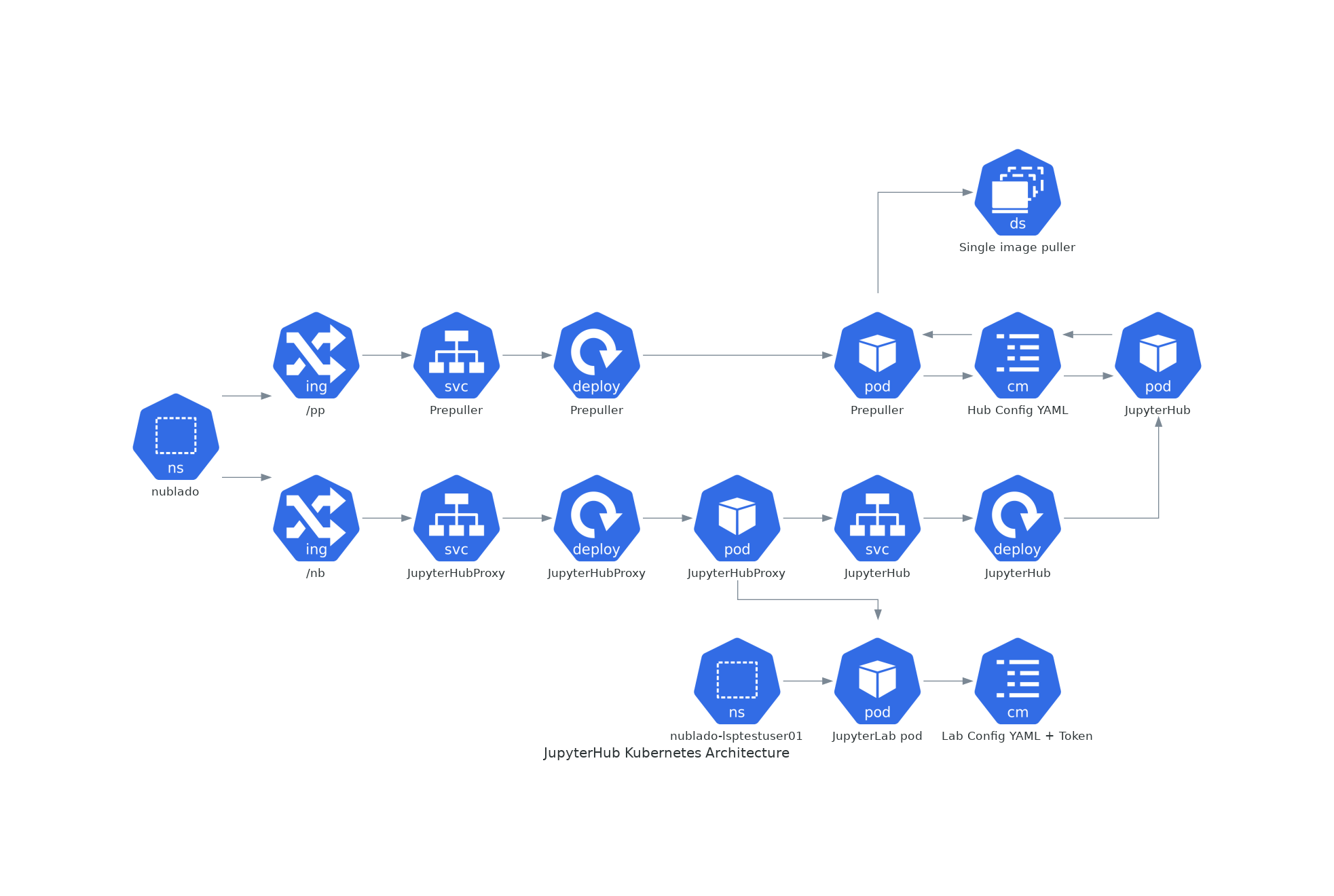

4 The Picture¶

5 Suggested Development Milestones and Order¶

This provides an order that should logically allow multiple developers to work together, and that important features are handled quickly and early, and we don’t have any feature creep or monolithic commits that are hard to debug.

6 Stage Zero¶

Okay, so we’re starting over. Let’s create a new empty repo and start from there.

Check in the Zero-To-JupyterHub chart to the repository. We will use this as the base of deployments and edit it as we add features.

Make a directory called docker that will contain our builds for the Docker containers. Start an empty container that inherits from the upstream JupyterHub container that works with the Zero-To-JupyterHub chart.

Set up pre-commits hooks for black and style checking.

Create a GitHub action that builds the containers in the docker directory, and pushes them to DockerHub.

Create a GitHub action that will kick the GKE environment and do a sync to the latest version of the created docker containers.

Setup Mobu to run login and python tests against the stock Jupyter. This will allow us to figure out if bugs are ours or possibly upstream.

Since we will be running the normal stock JupyterLab, and not our giant container, prepulling shouldn’t be an immediate problem.

Note: At this point, we might want to take a fork of this and allow Jupyter to take a look. It could be a useful combo with testing and Mobu, and we could at least run it against the latest stock versions of the Hub to figure out if it happens in stock Jupyter.

7 Stage One¶

7.1 Hub Configuration¶

All the configuration for the hub should be read from a single yaml file that is mounted into the container from a configmap. This allows us to change the configuration while still running without restarting the hub. Environment variables require a redeploy and many changes to the chart, and at the very least restarting the container.

Add this configmap to the chart and mount it in the hub.

7.2 Auth¶

Next, let’s do the authenticator. It doesn’t need to support anything but Gafaelfawr, and since all the headers should be present on the request, this shouldn’t require multiple callbacks or anything too complicated.

At this point, we should be able to spawn a lab with a name from the auth information. This should use the configuration available from the YAML file.

This can be done by implementing a Gafaelfawr authenticator class and using that for auth.

7.3 Lab Volume Mounting¶

Now let’s allow for the Lab containers that are spawned to have arbitrary volumes.

In the Hub YAML config file, there should be a key that contains two sub-documents for the volumes that will be injected into the pod manifest. This will allow for anyone to mount any volume into their pod, anywhere. This could be NFS, temporary space, or any supported kubernetes types. The format of these sub-documents will be injected directly into the pod YAML opaquely from the hub.

One subdocument will be volumes, and one is volumeMounts:

volumes:

- name: volume1

emptyDir: {}

- name: volume2

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: made-up-pvc-name

volumeMounts:

- name: volume1

mountPath: /scratch

- name: volume2

mountPath: /datasets

This will allow the Hub to create pods that can mount anything - volumes, configmaps, secrets, etc. This won’t allow for injection of environment variables, but will allow for file mapping.

Note: This doesn’t include _creation_ of volumes. This is just mounting them. Since all the lab pods are in the same namespace at this time, we should be able to create configmaps, volumes, and secrets in the namespace of the Hub, and have the Labs mount them.

At this point, we should have some ways to do configuration of the Hub (via the YAML file) and the Lab (via mounted configmaps). We can determine who the user is, and direct the right user to the right Lab.

This can probably be done by using the existing KubeSpawner.volumes and KubeSpawner.volume_mount options.

8 Stage Two¶

Now we can get ready for multiple and larger images.

8.1 Scanner¶

The scanner is a standalone python process that does NOT run in the Hub. It can be started via a crontab in the hub, or running a long running process in the container.

The scanner checks external information, such as the tags in docker, or external files, and outputs a YAML file that contains a list of images. The output should look like:

images:

- name: Recommended (this is weekly 38)

image: docker.io/lsstsqre/sciplatlab:weekly_38

- name: Weekly 38

image: docker.io/lsstsqre/sciplatlab:weekly_38

- name: Weekly 37

image: docker.io/lsstsqre/sciplatlab:weekly_37

- name: Daily 9/20

image: docker.io/lsstsqre/sciplatlab:d2020_09_20

The scanner will output this file on disk. By making a file on disk, this easily makes this a data passing problem rather than a library problem. The prepuller can then read the file for the source of things to prepull.

The scanner is something we can implement as a separate process from the Hub, that communicates its results by updating the JupyterHub YAML file. This can either be a process that runs in the JupyterHub container, or a separate pod.

8.2 Prepuller¶

The prepuller is also another standalone binary that runs in the hub container. This reads the file output of the scanner, and inspects nodes in kubernetes to see which images are available on which nodes. For images in the file the scanner generated, start pods to download those images. At the end of that, create a NEW YAML file that contains the images that are prepulled on all nodes.

The prepuller is something we can implement as a separate process from the Hub, and updates the JupyterHub YAML file. This can be a process that runs in the Hub container or a separate pod, and will spawn other pods to download the images.

8.3 Hub Options Form¶

The Hub Options form reads the YAML file that the prepuller outputs (or any other process, since it’s just a data file), and applies a template to generate an HTML page with the radio buttons to select images. This also allows for other parties to edit the template to add more boxes and options other than docker images.

For images that should show up in the options form but not be prepulled, this can be another YAML key in the file that is passed through the pipeline no matter what.

This allows also for easy static configuration of an options page for external parties who want an options form, but aren’t updating images frequently.

We can use the existing Kubespawner.options_form as a callable to implement the options form. This is a hook that is called with the spawner instance.

8.4 Stack Image Builder¶

We should create a GitHub action that runs daily to see if there’s a new stack image available, and build the Lab on top of it and push it to DockerHub. It’s best to try to get this out of Jenkins so we can see it running and change it more easily. We only have one connection point with Jenkins which is the stack container, and we only need to know when a new one is created.

8.5 Stack Image Reaper¶

We should create a GitHub action that contains the business logic to trim the images on dockerhub. This allows it to run in a centralized place, since we don’t want to run this per cluster, but match it with where the images are built.

There should be one reaper per set of images, not multiple reapers looking around for things to reap. If possible, we should have a good audit trail of the image deletions that are hopefully bubbled up through a GitHub action.

9 Stage Three¶

Now we can create larger images, that are prepulled with an options form. Now we want to get into the multinamespace factors and advanced configuration.

9.1 NamespacedKubeSpawner¶

Enable NamespacedKubeSpawner to spawn labs in individual namespaces.

This may require some changes to previous work, but otherwise should be fairly straightforward.

There are multiple PRs against JupyterHub by different teams to enable this. We should pick one, either ours or someone elses, and get it over the finish line. Being able to get the NamespacedKubeSpawner into Jupyter is key, and by enabling other groups to use the same code that we are using, we will be getting more options for free over time. We can always also propose more PRs to make the NamespaceKubeSpawner better over time.

9.2 Arbitrary Resource Creation¶

As a part of the lab creation process, first ensure that a list of resources exist. This list can be read from the Hub YAML file as sub-documents. A list of sub-documents can exist and be created in sequence if they do not exist.

This can be any type of resource, but they are all created in the namespace of the lab. This could enable people to create secrets, configmaps, other pods, etc. These resources will not be continually monitored by JupyterHub.

Once Labs are spawned in new namespaces, all those resources will need to be created when the namespace is created, we can’t rely on the zero to jupyterhub chart to create those resources in the shared namespace.

We should do this by injecting YAML, rather than special cases for every different type of resource. This will make it very easy to create arbitrary resources, even CRDs or other resource types that haven’t been invented yet.

The kubernetes python API provides a way to take arbitrary YAML and basically do a kubectl apply on it. This can be done by calling the kubernetes.util.create_from_yaml function.

We can insert this resource creation by using the Kubespawner.modify_pod_hook, which is a callable that is called with the spawner object, and the pod object to be created. There are also hooks for after the spawner stops (post_stop_hook) and before the spawner starts (pre_start_hook).

9.3 Culler¶

We need a working culler that will delete lab pods after a certain period of time. If we aren’t worried if the pods are active, then it is as easy as seeing when the pods were spawned. If this requires seeing when the pods were last active, we should figure out how to make sure that works in the new architecture as this is a feature provided by JupyterHub.

10 Further Work¶

10.1 Quota Service¶

Currently, all the quota restrictions are applied via the user namespace that is created that holds the lab pod. This limits the user from accidentally eating up all the resources in the cluster (via something like dask).

The other part of the quota is the machine size, although this is more against the counting against the quota, but this machine size is used in other places, since copying the size and image is the quickest way to get to a similar environment for the dask execution.

While setting a default size for a namespace is a good idea, and we should do that, this is only the beginning of the quota and scaling design. The general problem comes that Nublado can only really do things at spawn time, and during the existence of a lab pod, overall usage on the system may change.

My suggestion is to have a quota service that runs completely outside of Nublado. This could alter the resources on the namespace, growing them or shrinking them. This quota service could also provide policing and help for quota issues that Nublado doesn’t handle, things like in flight TAP queries, file system quotas, etc. We will want a central portal for both users to see where they are, and for admins and operators to temporarily change the numbers for particular users for a period of time. This could be thought of as a “processing allocation service.”